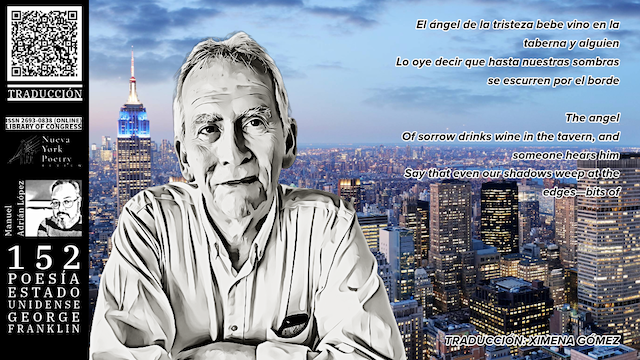

THE ANGEL OF SORROW DRINKS WINE IN THE TAVERN

A rat brushed its tail across your ankle when you were

Sewing, and now there are black lumps under your

Armpits, your mouth is dry, you shake with fever.

One above the other, bodies are piled into carts. The angel

Of sorrow drinks wine in the tavern, and someone hears him

Say that even our shadows weep at the edges—bits of

Ourselves slip away from us. You tell me you think

You’ll fall asleep and not wake when light makes

The dust visible on the window, when the sounds of men

Dragging out bodies disturb the sparrows and the crows.

Tomorrow, someone will seal the doorway with wax,

And the neighborhood dogs will lick at it till their tongues

Turn dark red and they grow bored. There will be no

Fire in the grate, and no smoke will twist from the chimney or

Crawl along the tiled roof or hide from the wind’s beak.

You ask me if the stars are visible in daytime, whether

The church doors glow now with a blue light, and if winged

Demons walk between the houses, looking for a way inside.

It’s a long time before I reply to you, kissing your cracked

Lips, tasting of fever and red clay, whispering all the lies

I can make up into your ears that are brittle as seashells.

There is no more clean water for your cup, no bread left

On the table, no stale oil in the jar by the stove. The candle by

Your bed went out last night. The wick is soot-grimed and curled.

I wrap your body in the sheet that covered your damp mattress

And sit in the dark waiting for the sound of wheels on

Cobblestones, the crush of corpses, one above the other.

In the tavern, the angel of sorrow will buy me a drink.

EL ÁNGEL DE LA TRISTEZA BEBE VINO EN LA TABERNA

Una rata te pasó la cola por el tobillo mientras cosías

Y ahora hay bultos negros debajo de tus sobacos,

Tienes la boca seca y estas temblando de fiebre.

Los cuerpos se amontonan unos sobre otros en carretas.

El ángel de la tristeza bebe vino en la taberna y alguien

Lo oye decir que hasta nuestras sombras se escurren por el borde

-Pedazos de nosotros se nos escapan. Me dices que piensas

Que te dormirás y no despertarás, cuando la luz haga visible

el polvo en la ventana, cuando el sonido de los hombres

Que arrastran cadáveres perturbe a los gorriones y a los cuervos.

Mañana alguien sellará la puerta con cera,

Y los perros del vecindario la lamerán hasta que sus lenguas

Queden de un rojo oscuro y se cansen. No habrá fuego

En la rejilla, ni el humo ondulará desde la chimenea, ni se

Escurrirá por el techo de tejas o se esconderá del pico del viento.

Me preguntas si las estrellas se ven de día, si las puertas

De la iglesia brillan ahora con una luz azul, y si los demonios

Alados caminan entre las casas, buscando la manera de entrar.

Pasó mucho tiempo antes de que yo te respondiera, te besara los labios

Rajados, con sabor a fiebre y a arcilla roja, susurrara todas las mentiras

Que pueda decirte en los oídos, que son frágiles como conchas del mar.

Ya no hay agua potable para tu taza, no queda pan en la mesa,

No hay aceite rancio en el frasco junto a la estufa. La vela junto

A tu cama se apagó anoche. La mecha está retorcida y llena de hollín.

Te envuelvo el cuerpo con la sábana que cubría tu colchón húmedo

Y me siento en la oscuridad, a esperar el sonido de las ruedas en

Los adoquines, los cadáveres que se aplastan uno sobre otro.

En la taberna, el ángel de la tristeza me invitará a un trago.

A FEW BLOCKS AWAY

Death likes a walk in the sunlight as much as anyone else. He prefers a trail that twists through old-growth forests and hillsides, or so he’s mentioned, but he’s fine with joining me here in late afternoon when the sun slides between driveways and houses and spreads long shadows on my narrow, suburban streets. Death says there’s something funny about people walking their dogs, especially when the dogs squat on the curb and look anxiously at the grass and sky. He’s tried to explain it to me, but I missed the humor. We both agree, though, that summer afternoons when the heat lets up are best. You wouldn’t think the heat would matter to Death, or the cold, but he shrugs and asks rhetorically, “If you can be comfortable, why not?” I’ve told him about my friend who died last year—a heart attack one night and dead by morning. Death says he remembers but would rather not discuss it. He says on a walk you shouldn’t talk shop.

A POCAS CUADRAS

A la muerte le gusta caminar bajo la luz del sol, como a cualquier persona. Prefiere un sendero que se meta entre los bosques centenarios y las laderas, o al menos eso es lo que me ha dicho, pero no le molesta acompañarme al atardecer, cuando el sol se filtra por los caminos de entrada y por las casas y proyecta sombras alargadas sobre las calles estrechas de los suburbios donde yo vivo. La muerte dice que la gente que pasea a sus perros tiene algo de chistoso, sobre todo cuando los perros se acurrucan en la acera y miran con ansiedad el pasto y el cielo. Ha tratado de explicármelo, pero no le veo la gracia. Sin embargo, ambos estamos de acuerdo en que las tardes de verano, a la hora en la que el calor baja, son las mejores. Uno no creería que el calor ni el frío pudieran afectarle a la Muerte, pero se encoge de hombros y hace una pregunta retórica: «¿Por qué no estar cómodo si uno puede?» Le hablé de mi amigo que murió el año pasado, al que le dio un infarto por la noche y por la mañana había muerto. La muerte dice que lo recuerda, pero que prefiere no hablar de eso. Dice que en una caminada no se debe hablar de cosas de trabajo.

THE BOOK THAT BURNS

In a field where medieval armies fought,

Abandoning their heavy weapons and their dead,

Now sunlight barely penetrates the canopy.

An overturned tree exposes moldy roots

And opens a hole it took five hundred years

For roots to dig. Water gone brackish, smelling

Of rotten leaves, gathers six feet deep, and a brown

Snake with black spots slides from circumference

To center and then returns. In the trunk of the tree,

Where it fell across what might have been a path,

There’s a large crack, cutting through both bark

And heartwood. I placed a book inside there once,

Wrapped in a cloth and purchased from a priest, or

At least he said he was a priest. If you try to take

The book with your bare hand, it will burn the skin

From your fingers. The book glows like red iron

In a fire, or perhaps you are the iron and the book

The fire. Perhaps, it is you who is glowing or burning.

The red letters burn as well. I don’t know what they say.

Their speech is the speech of those who left no pyramids

Or cathedrals, palaces or aqueducts. All that remains

Of them is this book written in the contradiction

Of fire and parchment, in letters no one alive can interpret.

There are no descendants of the authors, no sketches

On the walls of caves, no gravesites to be excavated.

Everything they were they put into their book.

This is a surmise. I know no more of its history than

Anyone else. Everything they were they turned to words

And trusted the words to survive them. Then they disappeared.

Not even the Sumerians knew they’d existed. They

Were successful: Their book still burns in the forest,

But it has no readers.

EL LIBRO ARDIENTE

Al campo donde los ejércitos de la Edad Media

Lucharon y abandonaron sus pesadas armas y sus muertos,

Ahora la luz del sol apenas entra por las copas de los árboles.

Un árbol caído deja al descubierto las raíces enmohecidas

Y abre un agujero que las raíces tardaron quinientos años

En cavar. El agua, ahora salobre, con olor a hojas podridas,

Se acumula a dos metros de profundidad

Y una serpiente marrón con manchas negras se desliza

Desde la circunferencia al centro y luego regresa.

Allí donde el tronco del árbol cayó, tal vez hubo un sendero,

Una enorme rajadura recorre la corteza

Y el duramen. Una vez puse ahí dentro un libro,

Que envolví en un paño y que le había comprado

A un sacerdote, o al menos eso dijo ser. Si tratas de coger

El libro con la mano desnuda te quemarás la piel de los dedos.

El libro brilla como hierro al rojo vivo en una hoguera,

O tal vez tú seas el hierro y el libro sea el fuego.

Tal vez seas tú quien brilla o arde. Las letras rojas

También arden. No sé lo que dicen.

Su idioma es el de aquellos que no dejaron pirámides,

Catedrales, palacios ni acueductos. Todo lo que queda

De ellos es este libro, escrito en la contradicción entre el fuego

Y el pergamino, en letras que ningún ser vivo puede interpretar.

No hay descendientes de sus autores, ni dibujos

En las paredes de las cavernas, ni tumbas que excavar.

Todo lo que fueron lo plasmaron en su libro.

Es una suposición. No conozco de su historia

Más que otros. Todo lo que fueron lo expresaron

En palabras y confiaron en que estas les sobrevivirían.

Luego desaparecieron. Ni siquiera los sumerios

Sabían que habían existido. Fueron exitosos.

Su libro aún arde en el bosque.

Pero no hay quien lo lea.

TOOTHACHE

Death has a toothache. He told me about it right before I went for a walk tonight. It’s not the kind of toothache that sends you to the dentist, but it’s more real than a metaphor. He complains that he’s unable to keep track of everywhere he has to be and when he has to be there. Time is being uncooperative. I don’t tell Death this, but there’s something reassuring about his toothache. It makes me more tolerant of my own distractions. There were so many things I had to do today, and so many of them were pushed back until tomorrow. Death holds his hand on his jaw to keep it warm. I ask if there’s anything I can do to help, but he shakes his head no. He tells me about the time John Donne had a toothache, but he kept writing right up until the barber arrived to pull it. I’m suitably embarrassed. I confess that I’ve written very little lately, and my teeth don’t hurt at all.

DOLOR DE MUELA

La muerte tiene dolor de muela. Me lo contó justo antes de salir a pasear por la noche. No es la clase de dolor que le obliga a uno a ir al dentista, pero es mucho más palpable que una simple metáfora. Se queja de que es incapaz de recordar dónde tiene que estar y a qué hora. El tiempo no le ayuda. Yo no se lo digo a la Muerte, pero hay algo que me tranquiliza de su dolor de muelas. Me hace más tolerante con mis propias distracciones. Tenía muchas cosas que hacer hoy y muchas de ellas se quedaron para mañana. La Muerte se pone la mano en la mandíbula para mantenerla tibia. Le pregunto si hay algo en lo que yo le pueda ayudar, pero niega con la cabeza. Me cuenta que a John Donne le dolía una muela, pero siguió escribiendo hasta que llegó el barbero para sacársela. Me siento avergonzado. Confieso que he escrito muy poco últimamente y no me duele ninguna muela.

Traducción: Ximena Gómez

George Franklin recibió el primer premio de poesía W.B. Yeats 2023 y es autor de seis poemarios: Remote Cities, Noise of the World, and Traveling for No Good Reason (https://tinyurl.com/Sheila-Na-Gig-Editions ), Travels of the Angel of Sorrow (https://tinyurl.com/Blue-Cedar-Press), Among the Ruins/Entre las ruinas, y un poemario del que es coautor con la poeta colombiana Ximena Gómez, Conversaciones sobre agua/Conversations About Water (https://tinyurl.com/Katakana-Editores ). Ha publicado, entre otras revistas, en: Rattle, Cagibi, New York Quarterly, The Ekphrastic Review, The Threepenny Review, Verse Daily y The American Journal of Poetry, y su obra ha aparecido traducida al español en Revista Abril, El Golem, Álastor, Nagari, Conexos y Suplemento de Realidades y Ficciones. Obtuvo una maestría en Poesía en la Universidad de Columbia, un doctorado en Literatura Inglesa y Americana en la Universidad de Brandeis y un título en Derecho en la Universidad de Miami. Ejerce la abogacía en Miami, imparte talleres de poesía en cárceles de la Florida y es co- traductor, junto con la autora, de Último día/Last Day, de Ximena Gómez. Su sitio web: https://gsfranklin.com/

Ximena Gómez, colombiana, nacida en Bogotá. Es autora de los poemarios: Habitación con moscas (Madrid: Ediciones Torremozas, 2016), Cuando llegue la sequía (Madrid: Ediciones Torremozas, 2021), de los poemarios bilingües Último día / Last Day (Miami, Katakana Editores, 2019) y otro en coautoría con George Franklin, Conversaciones sobre agua/Conversations About Water (Miami, Katakana Editores, 2023). Ha publicado sus poemas en: Álastor, Círculo de Poesía, Nueva York Poetry Review, Gulf Stream, El Golem, La raíz invertida, Baquiana, Nagari e Hypermedia, y traducidos al inglés en Cagibi, World Literature Today, Interim, Nashville Review, The Laurel Review y The Wild Word. Fue finalista al premio The Best of the Net y obtuvo el segundo lugar en el concurso anual de Gulf Stream. Es la traductora del poemario bilingüe Among the Ruins / Entre las ruinas, de George Franklin (Katakana Editores, 2018); Brown Girl Dreaming (Penguin Random House Group –2020) y Una para los Murphy (Miami: Penguin Random House Group – 2022). Fue co -traductora del poemario bilingüe 32 Poems/32 Poemas, de Hyam Plutzik (Miami: Suburbano Ediciones, 2021).